Expedition report

Report of an expedition through spaces of art and autonomy in Europe.

BLOG

9/3/20248 min read

At the end of July, Napoleon, Pavel and Dennis loaded an anvil, thongs, compressor, plasma cutter, welding machine and some hammers into the back of an old Peugeot for an 8.000 kilometer journey through Europe. This was not a trip. This was an expedition. An expedition with several objectives: to get to know other self-organized spaces and learn from them, to talk to blacksmiths, to make art, to decorate the world and to enjoy.

It was an expedition through zones and projects on the periphery of capitalism: self-organized art residencies, autonomous zones and post-capitalist colonies. One focus of the expedition was iron. I have written a book about how the iron industry reshaped our relation to space and time that should come out next year (Bloom; Iron and the Theft of Space and Time). Pavel Yakushev is an artist who makes street art out of steel. Napoleon is a ten-year-old blacksmith. All three of us enjoy banging metal into shape.

The culture of iron is a strange culture, a brotherhood almost: blacksmiths gladly help and host each other, and many of their artifacts circulate in the form of gifts. During this trip, we visited a number of our colleagues, each of them a unique artist with a vision all their own. In Bilbao, we spent a day forging in the workshop of Iñaki Olabarri. In Catalunya, we met Enric Pla Montferrer, the lead ironworker at the Sagrada Familia and an artist who makes iron looks like an organic material, and with Guillermina Morales, patron saint blacksmith of Barcelona’s Zona Roja. At Fantastic Factory we met up with Dzmitry Andreyeu, whose deep understanding of chemical processes allows him to make wonderful Damascus steel. In the ZAD we met Pierrot, a French blacksmith who was happy to share his workshop with us. Finally, in Osnabrück we attended the birthday party of Matthias Kühn, who made iron look like fabric in a series of life-sized works around the topic of depression.

We first set up our own mobile workshop in Calafou, an “ecoindustrial postcapitalist colony” on the outskirts of Barcelona. Calafou used to be an industrial colony where workers lived and worked, but it was long abandoned when a group of hackers and activists bought it in 2011. They set up a hackerspace, and our friend Pin set up a biolab to figure out what was going on with the smelly river – at the time one of the most polluted rivers in Europe. Calafou was conceived as a space of experimentation, with a huge workshop and lots of common areas. With time, the project consolidated itself: the space is owned by a cooperative, and its members live in private apartments. Inevitably, with time most inhabitants end up prioritizing their domesticity over communal experimentation – though one senses some nostalgia when they talk about the early days. We made a door handle and a big steel termite for a space called La Termita, that once a week functions as a bar to sell Calafou-brewn beer.

The next space where we set up shop is going through its own process of consolidation. The ZAD Notre-Dame-des-Landes began over a decade ago, when a number of French farmers refused to leave their homes to make way for the construction of an airport. For the government, ZAD meant Zone d’Aménagement Différé (deferred development area), a term that was given a new meaning by the activists that went there to block the eviction: now, ZAD means Zona à défendre, or Zone to Defend. The original ZAD in Notre-Dame occupies some 35 square kilometers and about 50 farming collectives. (Perhaps we should start thinking of starting a ZAD in Palas de Rei, or wherever Altri decides to put its factory?)

At the ZAD we set up our equipment in Pierrot’s blacksmith studio and worked with the motif of paper airplanes. With the help of Jay Jordan (who, together with their partner Isa Fremeaux, wrote an incredible book about the history of the ZAD), we welded a sculpture to the lighthouse that occupies the exact spot where the airport control tower should have been, had the government had its way. Like many of the ZAD’s improvised infrastructure, and like the forests and swamps around which the farms are built, this lighthouse served a defensive purpose in the guerilla war with the police. This is one of the few conflicts where the left won, not by swaying public opinion, but by being stronger in a direct confrontation with its adversary. After several failed eviction attempts the government was forced to cancel the airport in 2018. But while this was clearly a victory for the alliance “against an airport and its world,” it also spelled crisis for the ZADists. As the Zone to Defend no longer had an immediate threat from which to defend itself, its activist inhabitants were confronted with the question of long-term goals. Many of them have decided to stay to live a more ecological life and construct a world outside the progress-driven narratives of capitalist modernity, but some of the dynamism that marked the years of struggle will undoubtedly be lost as the area returns to its original agricultural use.

To maintain openness and experimentation and avoid turning into a commune – that is what I see as the main challenge of the Foundry these coming years. A commune prioritizes domesticity; people live their lives and share some of their space, perhaps even some care labour and resources, but as the inevitable stresses of life take over, the original impulse fades into the background (or people burn out trying to maintain that initial energy). It was with this in mind that we initially decided that people could not stay longer than a year at the Foundry. This may need to change, as the remoteness of Bravos has made it hard to sustain an international community that comes and goes.

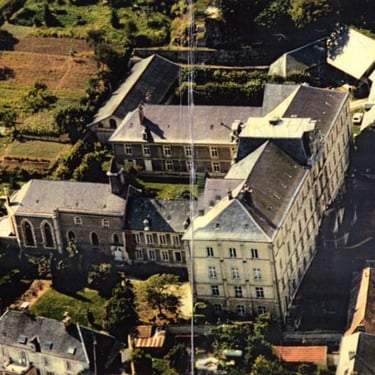

A project that seems to have successfully transitioned to self-organization while retaining its dynamism is PAF, the Performing Arts Forum in St. Erme between Paris and Brussels. PAF has served as an inspiration for the Foundry for years; I have visited it four or five times, and its founder Jan Ritsema (RIP) helped me with some legal details. On this adventure it was the third place where we set up our workshop. PAF is enormous: it’s an old monastery with about 70 bedrooms, and it can host over 100 people. Its relation to the neighbours is precarious; I’ve never seen someone from the village in PAF, and contact with the villagers is not encouraged – but perhaps it is precisely PAF’s fort-like nature that secures the micro-utopia inside. PAF puts some effort into maintaining itself as a space of work rather than a domestic space – until a few years ago, children were not allowed there, and users usually don’t stay for years at a time. The space is owned by 50 shareholders, and sustained by an international community, receiving about 2000 visitors each year. Internally, it is organized by means of four principles, some of which we have simply copied when formulating our vision for the Foundry: 1. The doer decides; 2. Make things possible for others; 3. Don’t leave traces; and 4. Mind asymmetries. Together, they have secured a highly dynamic and safe space for artistic experimentation.

Because of the third principle, we did not leave any street art at PAF, though they did ask us to forge a few fence posts, and Pavel made an anti-war artwork using one of the helmets we were gifted at the ZAD. We fixed this work at the last stop for our workshop: MaHalla, an old machine factory that once served as an inspiration for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and has now become a center for art and spirituality in Berlin, of which me and Napoleon are co-owners. MaHalla is neither self-organized nor anti-capitalist – it seems that the pressures generated by the need to pay the rent make it almost impossible to do anything radical and space-based in a city like Berlin (isn’t that what brought us to Galicia?). Be that as it may, in this most distant stop of our expedition, we fixed a war helmet and some birds to a steel pillar.

As an anarchist, I have long been interested in the construction of counter-infrastructure. With this term I refer to infrastructure that is not plugged into the world of state and capital, but exists on the periphery of that world. And there’s a lot of it: the last decades have witnessed an explosion of eco-villages, squats, temporary autonomous zones, ZADs, and other free spaces that position themselves as an alternative to the capitalist world order. I have tried to build the Foundry as a small part of that infrastructure: a cheap and accessible space where artists and other creators can do their work without being distracted by bureaucratic hurdles and experiment with forms-of-life that struggle to find a place in the patriarchal neoliberal order.

A project like that has a whole world to fight with, and while I believe we have achieved a lot in the six years since it started, there are also plenty of unresolved issues. Due to its remoteness the Foundry has not developed an international community on which it can fall back (like PAF). Due to the limits on maximum stays, navigating the balance between openness and continuity remains more challenging than in spaces that allow people to live there forever (like Calafou and the ZAD). People have burned out and withdrawn from the Foundry. Deciding everything in assemblies is time-consuming, and in a world where monetary incentives reign, it’s hard to motivate people without them. I have perhaps overestimated the need for this type of space in the international art world, and underestimated the desire for people to simply “leave the system”: about ten houses nearby have been bought by former Foundry residents. Obviously, neighbors prioritize their domesticity, and their needs do not always align with a project like the Foundry, which depends on a steady flow of people to retain its dynamism and sustain itself financially (although sometimes it is precisely this dynamism that wears us out). These problems have not been resolved, and I do not think they can be without sacrificing the nature of the project (open, self-organized, non-profit).

As some people that frequent the Foundry know, I am planning to move back to Berlin early next year, and I no longer want to take an active role in managing the Foundry. But I do hope the space continues to develop without becoming a commune. Perhaps groups of people that need space to develop their project can occupy the Foundry for about two years each, generating a modest income for themselves while curating the space and organizing events. If these groups change every few years, they won’t appropriate the space, which would hopefully remain open for work that is not valued by the market.

I still dream of a network of autonomous spaces, that together could promote collective self-sufficiency without relying on global markets, and I believe the need for these kinds of spaces will only increase in the decades to come. During our expedition, we have visited some of these spaces, where many people work to make other worlds possible. The world of state and capital sacrifices the common good on the altar of private interest. There is a book about the ZAD called “We are Nature Defending Itself” - defending itself from the capitalist hydra, that sometimes shows itself in the guise of an airport, sometimes in the guise of a Lyocell factory that turns our forests into plantations and pollutes our rivers. The ZAD is a crack in the neoliberal world order, but there are many cracks, and if we widen and connect them, one day we will rob capital of its main pillar of support: the false idea that “There Is No Alternative” (Margaret Thatcher). As our friend David Graeber once said: “The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”